Vulvar Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

This summary addresses squamous cell cancer of the vulva and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasias (VIN), some of which are thought to be precursors to invasive squamous cell cancers.

The labia majora are the most common sites of vulvar carcinoma and account for about 50% of cases. The labia minora account for 15% to 20% of vulvar carcinoma cases. The clitoris and Bartholin glands are less frequently involved.[1] Lesions are multifocal in about 5% of cases. More than 90% of invasive vulvar cancers are squamous cell carcinomas.[2]

Incidence and Mortality

Vulvar cancer accounts for about 6% of cancers of the female genital system in the United States.[3]

Estimated new cases and deaths from vulvar cancer in the United States in 2024:[3]

- New cases: 6,900.

- Deaths: 1,630.

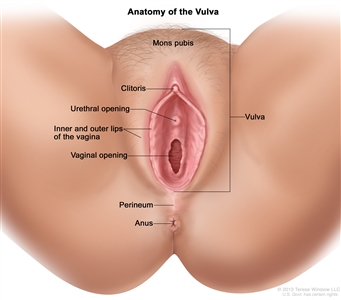

Anatomy

The vulva is the area immediately external to the vagina, including the mons pubis, labia, clitoris, and Bartholin glands.

Anatomy of the vulva. The vulva includes the mons pubis, clitoris, inner and outer lips of the vagina, and the openings of the urethra and vagina.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors associated with vulvar cancer include the following:

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection: In many cases, the development of vulvar cancer is preceded by condyloma or squamous dysplasia. The prevailing evidence favors HPV infection as a causative factor in many genital tract carcinomas.[4]

HPV-associated VIN, termed usual-type VIN when high grades 2 and 3, is most common in women younger than 50 years, whereas non-HPV VIN, termed differentiated-type VIN when high grade 3, is most common in older women.[5,6]

The former lesion-type VIN grade 1 is no longer classified as a true VIN.[5,6] The HPV-related basaloid and warty types are associated with VIN. About 75% to 100% of basaloid and warty carcinomas harbor HPV infection. In addition to the much higher prevalence of HPV in these subtypes than in the keratinizing subtypes, the basaloid and warty subtypes also share many common risk factors with cervical cancers, including the following:

For more information, see Cervical Cancer Treatment.

Clinical Features

Women with VIN may not present with symptoms at diagnosis.

Possible signs and symptoms of invasive squamous cell cancers of the vulva include the following:

- Vulvar lesion.

- Vulvar pruritus.

- Bleeding.

- Pain.

Diagnostic and Staging Evaluation

The following procedures may be used to diagnose and stage vulvar cancer:

- Physical examination and history.

- Pelvic examination.

- Pap smear.

- HPV testing.

- Biopsy. The patient may be examined under anesthesia.

- Colposcopy.

- Imaging studies (magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography [CT], and positron emission tomography-CT).

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the pathological status of the inguinal lymph nodes and whether spread to adjacent structures has occurred.[8] In patients with operable disease without lymph node involvement, the overall survival (OS) rate is 90%. However, in patients with nodal involvement, the 5-year OS rate is approximately 50% to 60%.[9]

The size of the primary tumor is less important in defining prognosis.[8]

Follow-Up After Treatment

Invasive and preinvasive neoplasms of the vulva may be HPV-induced, and the carcinogenic effect may be widespread in the vulvar epithelium. As a result, patients are monitored regularly for signs or symptoms of recurrence.

References:

- Macnab JC, Walkinshaw SA, Cordiner JW, et al.: Human papillomavirus in clinically and histologically normal tissue of patients with genital cancer. N Engl J Med 315 (17): 1052-8, 1986.

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2024. American Cancer Society, 2024. Available online. Last accessed June 21, 2024.

- Hampl M, Sarajuuri H, Wentzensen N, et al.: Effect of human papillomavirus vaccines on vulvar, vaginal, and anal intraepithelial lesions and vulvar cancer. Obstet Gynecol 108 (6): 1361-8, 2006.

- Pepas L, Kaushik S, Bryant A, et al.: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD007924, 2011.

- Sideri M, Jones RW, Wilkinson EJ, et al.: Squamous vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: 2004 modified terminology, ISSVD Vulvar Oncology Subcommittee. J Reprod Med 50 (11): 807-10, 2005.

- Schiffman M, Kjaer SK: Chapter 2: Natural history of anogenital human papillomavirus infection and neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr (31): 14-9, 2003.

- Olawaiye AB, Hagemann I, Bhoshale P, et al.: Vulva. In: Goodman KA, Gollub M, Eng C, et al.: AJCC Cancer Staging System. Version 9. American Joint Committee on Cancer; American College of Surgeons, 2023.

- Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al.: Assessment of current International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging of vulvar carcinoma relative to prognostic factors for survival (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). Am J Obstet Gynecol 164 (4): 997-1003; discussion 1003-4, 1991.

The histological classification of vulvar disease and precursor lesions of cancer of the vulva was developed by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD).[1]

Nonneoplastic epithelial disorders of vulvar skin and mucosa

- Lichen sclerosus (lichen sclerosus et atrophicus).

- Squamous cell hyperplasia (formerly hyperplastic dystrophy).

- Other dermatoses.

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) of the vulva (vulvar LSIL) encompasses flat condyloma or human papillomavirus effect.

- High-grade SIL (vulvar HSIL) was termed VIN, usual type in the 2004 ISSVD terminology.

- VIN, differentiated type.

Paget disease of the vulva

- Characteristic large pale cells in the epithelium and skin adnexa.

Other histologies

- Basal cell carcinoma.

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

- Malignant melanoma.

- Sarcoma.

- Verrucous carcinoma.

References:

- Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, et al.: The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Terminology of Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. J Low Genit Tract Dis 20 (1): 11-4, 2016.

Staging evaluation for vulvar cancer may include the following:

- Cystoscopy.

- Proctoscopy.

- X-ray examination of the lungs.

- Intravenous (IV) urography (also known as IV pyelography).

Suspected bladder or rectal involvement must be confirmed by biopsy.[1]

The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) Staging

FIGO and the American Joint Committee on Cancer have designated staging to define vulvar cancer; the FIGO system is most commonly used.[1,2] Stage is based on pathological staging at the time of surgery or before any radiation or chemotherapy, if they are the initial treatment modalities.[3]

The staging system does not apply to malignant melanoma of the vulva, which is staged like melanoma of the skin.[1] For more information, see the Stage Information for Melanoma section in Melanoma Treatment.

| Stage | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | ||

| b Depth of invasion is measured from the basement membrane of the deepest, adjacent, dysplastic, tumor-free rete ridge (or nearest dysplastic rete peg) to the deepest point of invasion. | ||

| I | Tumor confined to the vulva. | |

| IA | Tumor size ≤2 cm and stromal invasion ≤1 mmb. | |

| IB | Tumor size >2 cm or stromal invasion >1 mmb. | |

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | |

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | |

| II | Tumor of any size with extension to lower one-third of the urethra, lower one-third of the vagina, lower one-third of the anus with negative nodes. |

| Stage | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | ||

| b Regional refers to inguinal and femoral lymph nodes. | ||

| III | Tumor of any size with extension to upper part of adjacent perineal structures, or with any number of nonfixed, nonulcerated lymph nodes. | |

| IIIA | Tumor of any size with disease extension to upper two-thirds of the urethra, upper two-thirds of the vagina, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, or regional lymph node metastases ≤5 mm. | |

| IIIB | Regionalb lymph node metastases >5 mm. | |

| IIIC | Regionalb lymph node metastases with extracapsular spread. | |

| Stage | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | ||

| b Regional refers to inguinal and femoral lymph nodes. | ||

| IV | Tumor of any size fixed to bone, or fixed, ulcerated lymph node metastases, or distant metastases. | |

| IVA | Disease fixed to pelvic bone,or fixed or ulcerated regionalb lymph node metastases. | |

| IVB | Distant metastases. | |

Grade is reported in registry systems and may differ between systems; a two-, three-, or four-grade system may be applied. If not specified, the following system is generally used:[1]

- GX: Grade cannot be assessed.

- G1: Well differentiated.

- G2: Moderately differentiated.

- G3: Poorly differentiated.

Overall, about 30% of patients with operable disease have lymph node spread. The pattern of spread is influenced by the histology. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis include the following:[4,5,6,7,8]

- Clinical node status.

- Age.

- Degree of tumor differentiation.

- Tumor stage.

- Tumor thickness.

- Depth of stromal invasion.

- Presence of capillary-lymphatic space invasion.

Well-differentiated lesions tend to spread along the surface with minimal invasion, whereas anaplastic lesions are more likely to be deeply invasive. Spread beyond the vulva is either to adjacent organs such as the vagina, urethra, and anus, or via the lymphatics to the inguinal and femoral lymph nodes, followed by the deep pelvic nodes. Hematogenous spread appears to be uncommon.

References:

- Olawaiye AB, Hagemann I, Bhoshale P, et al.: Vulva. In: Goodman KA, Gollub M, Eng C, et al.: AJCC Cancer Staging System. Version 9. American Joint Committee on Cancer; American College of Surgeons, 2023.

- Olawaiye AB, Cuello MA, Rogers LJ: Cancer of the vulva: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 7-18, 2021.

- Hopkins MP, Reid GC, Johnston CM, et al.: A comparison of staging systems for squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 47 (1): 34-7, 1992.

- Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al.: Assessment of current International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging of vulvar carcinoma relative to prognostic factors for survival (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). Am J Obstet Gynecol 164 (4): 997-1003; discussion 1003-4, 1991.

- Boyce J, Fruchter RG, Kasambilides E, et al.: Prognostic factors in carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 20 (3): 364-77, 1985.

- Sedlis A, Homesley H, Bundy BN, et al.: Positive groin lymph nodes in superficial squamous cell vulvar cancer. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 156 (5): 1159-64, 1987.

- Binder SW, Huang I, Fu YS, et al.: Risk factors for the development of lymph node metastasis in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 37 (1): 9-16, 1990.

- Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al.: Prognostic factors for groin node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study) Gynecol Oncol 49 (3): 279-83, 1993.

The primary treatment for vulvar cancer is surgery. Radiation therapy is also given to patients with stage III or IV disease.[1,2,3] Newer strategies have integrated surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy and tailor the treatment to the extent of clinical and pathological disease. Patterns of practice in combining these treatments vary.[4]

Because there are few patients with advanced disease (stages III and IV), only limited data are available on treatment efficacy in this setting, and there is no standard chemotherapy regimen for these patients. Physicians may offer eligible patients with stage III or IV disease participation in clinical trials.

Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

| Stage ( FIGO Staging Criteria) | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique; VIN = vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. | |

| VIN (this stage is not recognized by FIGO) | Surgery |

| Topical imiquimod | |

| Stages I and II vulvar cancer | Surgery |

| Surgery and radiation therapy | |

| Radiation therapy alone | |

| Stage III vulvar cancer | Surgery with or without radiation therapy |

| Radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery | |

| Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy | |

| Stage IVA vulvar cancer | Surgery |

| Surgery and radiation therapy | |

| Radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery | |

| Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy | |

| Stage IVB vulvar cancer | Chemotherapy |

| Recurrent vulvar cancer | Wide local excision with or without radiation therapy |

| Radical vulvectomy and pelvic exenteration | |

| Synchronous radiation therapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy with or without surgery | |

Surgery

Surgical resection

Since the 1980s, the trend of surgical resection in patients with vulvar cancer has been toward more limited surgery, often combined with radiation therapy to minimize morbidity.[5] In tumors clinically confined to the vulva or perineum, radical local excision with a margin of at least 1 cm has generally replaced radical vulvectomy; separate incision has replaced en bloc inguinal lymph node dissection; ipsilateral inguinal node dissection has replaced bilateral dissection for laterally localized tumors; and femoral lymph node dissection has been omitted in many cases.[2,5,6,7] However, the different surgical techniques have not been directly compared in randomized controlled trials. In addition, nonrandomized studies lack uniform staging definitions and clear descriptions of lymph node dissection or ancillary radiation.[8][Levels of evidence C2 and C3] The evidence base is, therefore, limited.

Sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND)

Another strategy to minimize the morbidity incurred by groin lymph node dissection in patients with early clinical-stage disease is SLND, reserving groin dissection for those with metastases to the sentinel node(s).

Evidence (SLND):

- In a multicenter case series, 403 patients with primary vulvar squamous cell cancers smaller than 4 cm and clinically negative groin lymph nodes underwent 623 SLNDs (using radioactive tracer and blue dye for sentinel node identification).[9] All patients had radical resection of the primary tumor. Node metastases were identified in 26% of SLND procedures, and these patients went on to full inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. The patients with negative sentinel nodes received no further therapy. After two local recurrences in 17 patients with multifocal primary tumors, the protocol was amended to allow only patients with unifocal tumors into the study.[9][Level of evidence C3]

- Local morbidity was much lower in patients who underwent SLND than in patients with positive sentinel nodes who also underwent inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (see Table 6).

Table 6. Comparisona of Local Morbidity in Patients Treated With SLND Versus SLND and Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy Complications Local Morbidity From SLND (%) Local Morbidity From SLND and Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy (%) SLND = Sentinel lymph node dissection. aP< .0001 for all comparisons. Wound breakdown 11.7 34 Cellulitis 4.5 21.3 Chronic lymphedema 1.9 25.2 - The mean hospital stay was 8.4 days for patients who underwent SLND and 13.7 days for patients who underwent SLND and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (P < .0001).

- The actuarial groin recurrence rate for all patients with negative SLND results at 2 years was 3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1%–6%) and 2% (95% CI, 1%–5%) for those with unifocal primary tumors.

- Local morbidity was much lower in patients who underwent SLND than in patients with positive sentinel nodes who also underwent inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (see Table 6).

SLND may be useful when performed by a surgeon experienced in the procedure, and it may avoid the need for full groin lymph node dissection or radiation therapy in patients with clinically nonsuspicious lymph nodes.

Radiation Therapy

Radical radiation therapy can be used for patients unable to tolerate surgery or when surgery is not an option because of the site or extent of disease.[10,11,12,13]

Groin lymph node metastases are present in approximately 20% to 35% of patients with tumors clinically confined to the vulva and with clinically negative nodes.[9,14] Lymph node dissection is traditionally part of the primary surgical therapy in all but the smallest tumors. Some investigators recommend radiation therapy as a means to avoid the morbidity of lymph node dissection, but it is not clear whether radiation therapy can achieve the same local control rates or survival rates as lymph node dissection in early-stage disease.

Localized node-negative disease

A randomized trial to address the efficacy of radiation therapy in patients with clinically localized vulvar cancer has been reported.[14,15] In that study, women with disease clinically confined to the vulva, who did not have clinically suspicious groin lymph node metastases, underwent radical vulvectomy followed by either groin radiation (50 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction) or groin dissection (plus groin radiation if nodes were pathologically involved). Although the planned accrual was 300 patients, the study was stopped after 58 women were randomly assigned because of worse outcomes in the radiation therapy arm.

- Five of 27 (18.5%) women in the radiation therapy arm and 0 of 25 women in the groin dissection arm had a groin recurrence, but this difference was not statistically significant (relative risk [RR], 10.21; 95% CI, 0.59–175.78).

- There were ten deaths in the radiation therapy arm and three deaths in the groin dissection arm (RR, 4.31; 95% CI, 1.03–18.15).

- Disease-specific mortality was not statistically significantly different between the two arms. However, there were eight vulvar cancer–related deaths in the radiation therapy arm versus two vulvar cancer–related deaths in the groin dissection arm (including one related to the groin dissection surgery) (RR, 3.70; 95% CI, 0.87–15.80).[14,15][Level of evidence A1]

- There were fewer cases of lymphedema (none in the radiation therapy arm vs. seven in the groin dissection arm) and shorter hospital stays in the radiation therapy arm. The dose penetration of the radiation (3 cm for full dose) has been criticized as inadequate.[14]

In summary, the trial was stopped prematurely, and little can be said about the relative efficacy of the two treatment approaches.[14]

Pelvic node–positive disease

Pelvic radiation therapy has been compared with pelvic node resection in patients with documented groin node–positive disease.

Evidence (pelvic node resection vs. pelvic radiation therapy):

- Patients with clinical stage I to stage IV primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva in whom groin node metastases were found at radical vulvectomy and bilateral groin lymph node dissection were randomly assigned (during the surgical procedure) to receive either ipsilateral pelvic node resection or pelvic radiation therapy (45 Gy–50 Gy at 1.8 Gy–2.0 Gy per fraction).[16] Because of a perceived emerging benefit of radiation therapy, the planned accrual of 152 patients was stopped after 114 patients were randomly assigned. However, the apparent benefit of radiation was subsequently attenuated with further follow-up.[16][Level of evidence A1]

- After a median follow-up of 74 months, the 6-year overall survival (OS) rate was 51% in the pelvic radiation therapy arm versus 41% in the pelvic node resection arm (hazard ratio [HR], 0.61; 95% CI, 0.3–1.3; P = .18).

- Vulvar cancer–specific mortality was statistically significantly lower in the pelvic radiation therapy arm (29% in the pelvic radiation therapy arm vs. 51% in the pelvic node resection arm) (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28–0.87; P = .015). However, there were 14 intercurrent deaths in the pelvic radiation therapy arm versus two deaths in the pelvic node resection arm.

- Late chronic lymphedema was similar in both trial arms with 16% in the pelvic radiation therapy arm and 22% in the pelvic node resection arm.

Chemotherapy

There is no standard chemotherapy for vulvar cancer, and reports describing the use of this modality in the setting of metastatic or recurrent disease are anecdotal.[5]

Extrapolating from regimens used for anal or cervical squamous cell cancers, chemotherapy has been studied in combination with radiation in the neoadjuvant setting or as primary therapy in advanced disease. Chemotherapy regimens have included various combinations of fluorouracil (5-FU), cisplatin, mitomycin, or bleomycin.[5]

There is no clear evidence of improvement in survival or palliation. Given the advanced age and comorbidities of many patients with advanced or recurrent vulvar cancer, patient tolerance is a major consideration in the use of these agents.

Systemic treatment for inoperable patients

A systematic review of the use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy in patients who were considered inoperable or who would have required extensive surgery, such as pelvic exenteration, colostomy, or urinary diversion, revealed no randomized trials.[17] Five nonrandomized studies that met the inclusion criteria of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy administered in this population with an intent to permit curative surgery were reviewed.[18,19,20,21,22] The five studies used four different chemoradiation therapy schedules and different radiation therapy dose-fractionation techniques. In the four studies using 5-FU with either cisplatin or mitomycin, the operability rate after chemoradiation therapy ranged from 63% to 92%.[18,19,20,21] In the one study using bleomycin, the operability rate was only 20%.[22]

In summary, there is evidence that neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy with 5-FU plus either cisplatin or mitomycin may convert patients to a more operable status, but the evidence base is limited by study design. In addition to a paucity of randomized trials, interpretation of these studies is complicated by the lack of a standard definition of operability.[4][Level of evidence C3] Treatment-related toxicity is substantial.

Systemic treatment for operable patients

There is limited evidence about the use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy in advanced operable vulvar cancer, and the available data do not suggest an advantage to this approach. A systematic review found only one randomized trial that addressed this issue, and it was published only in abstract form.[4,23] In that trial, 68 patients with advanced vulvar cancer (T2* >4 cm, T3*, any case with positive lymph nodes) were randomly assigned to either receive preoperative neoadjuvant radiation therapy (50 Gy) concomitantly with 5-FU and mitomycin or primary surgery. Neoadjuvant therapy–related serious toxicity was high (13 of 24 patients; 10 patients had wound diastasis). After a mean follow-up of 42 months, the 5-year OS rate was 30% in the neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy arm and 49% in the primary surgery arm (RRdeath, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.94–2.06; P = .19).[4,23][Level of evidence A1] *T2 is defined as tumor confined to the vulva and/or perineum, more than 2 cm in greatest dimension, and T3 is defined as tumor that invades any of the following: the lower urethra, vagina, or anus.

Fluorouracil dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[24,25] Patients with the DPYD*2A variant who receive fluoropyrimidines may experience severe, life-threatening toxicities that are sometimes fatal. Many other DPYD variants have been identified, with a range of clinical effects.[24,25,26] Fluoropyrimidine avoidance or a dose reduction of 50% may be recommended based on the patient's DPYD genotype and number of functioning DPYD alleles.[27,28,29]DPYD genetic testing costs less than $200, but insurance coverage varies due to a lack of national guidelines.[30] In addition, testing may delay therapy by 2 weeks, which would not be advisable in urgent situations. This controversial issue requires further evaluation.[31]

References:

- Hacker NF, Van der Velden J: Conservative management of early vulvar cancer. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1673-7, 1993.

- Thomas GM, Dembo AJ, Bryson SC, et al.: Changing concepts in the management of vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol 42 (1): 9-21, 1991.

- Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al.: Radiation therapy versus pelvic node resection for carcinoma of the vulva with positive groin nodes. Obstet Gynecol 68 (6): 733-40, 1986.

- Shylasree TS, Bryant A, Howells RE: Chemoradiation for advanced primary vulval cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003752, 2011.

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

- Hoffman MS, Roberts WS, Lapolla JP, et al.: Recent modifications in the treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol Surv 44 (4): 227-33, 1989.

- Heaps JM, Fu YS, Montz FJ, et al.: Surgical-pathologic variables predictive of local recurrence in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 38 (3): 309-14, 1990.

- Ansink A, van der Velden J: Surgical interventions for early squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD002036, 2000.

- Van der Zee AG, Oonk MH, De Hullu JA, et al.: Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early-stage vulvar cancer. J Clin Oncol 26 (6): 884-9, 2008.

- Petereit DG, Mehta MP, Buchler DA, et al.: Inguinofemoral radiation of N0,N1 vulvar cancer may be equivalent to lymphadenectomy if proper radiation technique is used. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 27 (4): 963-7, 1993.

- Slevin NJ, Pointon RC: Radical radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Radiol 62 (734): 145-7, 1989.

- Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Galakatos A, et al.: Radiation therapy in management of carcinoma of the vulva with emphasis on conservation therapy. Cancer 71 (11): 3707-16, 1993.

- Kumar PP, Good RR, Scott JC: Techniques for management of vulvar cancer by irradiation alone. Radiat Med 6 (4): 185-91, 1988 Jul-Aug.

- Stehman FB, Bundy BN, Thomas G, et al.: Groin dissection versus groin radiation in carcinoma of the vulva: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 24 (2): 389-96, 1992.

- van der Velden J, Fons G, Lawrie TA: Primary groin irradiation versus primary groin surgery for early vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5): CD002224, 2011.

- Kunos C, Simpkins F, Gibbons H, et al.: Radiation therapy compared with pelvic node resection for node-positive vulvar cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 114 (3): 537-46, 2009.

- van Doorn HC, Ansink A, Verhaar-Langereis M, et al.: Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for advanced primary vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD003752, 2006.

- Eifel PJ, Morris M, Burke TW, et al.: Prolonged continuous infusion cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with radiation for locally advanced carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 59 (1): 51-6, 1995.

- Landoni F, Maneo A, Zanetta G, et al.: Concurrent preoperative chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C and radiotherapy (FUMIR) followed by limited surgery in locally advanced and recurrent vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 61 (3): 321-7, 1996.

- Montana GS, Thomas GM, Moore DH, et al.: Preoperative chemo-radiation for carcinoma of the vulva with N2/N3 nodes: a gynecologic oncology group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 48 (4): 1007-13, 2000.

- Moore DH, Thomas GM, Montana GS, et al.: Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 42 (1): 79-85, 1998.

- Scheiströen M, Tropé C: Combined bleomycin and irradiation in preoperative treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Acta Oncol 32 (6): 657-61, 1993.

- Maneo A, Landoni F, Colombo A, et al.: Randomised study between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and primary surgery for the treatment of advanced vulvar cancer. [Abstract] Int J Gynecol Cancer 13 (Suppl 1): A-PL19, 6, 2003.

- Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021.

- Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016.

- Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021.

- Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018.

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018.

- Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022.

- Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022.

- Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023.

Treatment Options for VIN

Treatment options for VIN include the following:

- Surgery.

- Separate excision of focal lesions.[1]

- Wide local excision.[1]

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser surgery and vaporization.[2,3] A disadvantage of vaporization is that it does not provide tissue for histological examination to confirm complete removal of the lesion and the absence of invasive disease.

- Ultrasonic surgical aspiration.[2,3]

- Superficial skinning vulvectomy with or without grafting.[1]

- Topical imiquimod for patients who want to avoid surgery.[4,5,6,7,8]

Traditionally, there were three grades of VIN, however, there is little evidence that all three grades are part of the same biological continuum or that grade 1 is even a cancer precursor. In 2004, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) changed its terminology, reserving the designation VIN for two categories of lesions based on morphological appearance.[9] In 2015, the ISSVD developed terminology for vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL), which includes the following:[10]

- Low-grade SIL of the vulva (vulvar LSIL) encompasses flat condyloma or human papillomavirus effect.

- High-grade SIL (vulvar HSIL) was termed VIN, usual type in the 2004 ISSVD terminology.

- VIN, differentiated type.

High-grade VIN is usually managed with active therapy because of a higher risk for progression to invasive disease.[2] Estimates of progression rates are imprecise. A systematic literature review that included 88 untreated patients with VIN 3 reported a 9% progression rate (8 of 88 patients) to invasive vulvar cancer during 12 to 96 months of observation. In the same review, the spontaneous regression rate was 1.2%, all of which occurred in women younger than 35 years.[1] However, in a single-center study, 10 of 63 (16%) untreated women with VIN 2 or VIN 3 progressed to invasive cancer after a mean of 3.9 years.[11]

VIN lesions may be multifocal or confluent and extensive. It is important to perform multiple biopsies in treatment planning to exclude occult invasive disease. VIN located in nonhairy areas can be considered an epithelial disease; however, VIN found in hairy sites usually involves the pilosebaceous apparatus and requires a greater depth of excision because it can track along hair roots.

Surgery

The principal treatment approach is surgery, but there is no consensus on the optimal surgical procedure. The goal is to remove or destroy the entire VIN lesion while preserving vulvar anatomy and function. Simple vulvectomy yields a 5-year survival rate of nearly 100% but is seldom indicated. Other more limited surgical procedures, including separate excision of multiple lesions, are less deforming.[12] The choice of treatment depends on the extent of the disease and the experience of the treating physician. There are no reliable data comparing the efficacy and safety of the various surgical approaches.

A systematic literature review identified only a single randomized trial comparing any of the surgical approaches.[2] In that trial, 30 women with high-grade VIN were randomly assigned to either receive CO2 laser ablation or ultrasound surgical aspiration.[3] There were no statistically significant differences in disease recurrence, painful dysuria or burning, adhesions, or eschar formation between the two treatments after 1 year of follow-up. Scarring was observed in 5 of 16 women treated with laser ablation and 0 of 14 women treated with ultrasound surgical aspiration (P < .01), but consequences of the scarring on sexual function or quality of life were not reported.[3][Level of evidence B1] The trial was too small to draw reliable conclusions about the relative efficacy of these surgical techniques. The remainder of the surgical literature is derived from case series and is prone to important study biases.[Level of evidence C2]

Whatever procedure is used, patients are at substantial risk of recurrence, particularly when the lesions are high grade or multifocal.[13] The most common sites of recurrence are the perianal skin, presacral area, and clitoral hood. About 4% of patients treated for VIN subsequently develop invasive cancer.[14,15]

Nonsurgical interventions

Topical imiquimod

Among women with high-grade VIN, substantial response rates and acceptable tolerability were reported for topical imiquimod 5%, an immune-response modifier with activity in human papillomavirus types 6- and 11-associated vulvar condylomata.

Evidence (imiquimod):

- Three randomized placebo-controlled trials (including a total of 104 patients) with clinical response as the primary end points have been reported in either peer-reviewed-journals or in abstract format.[7];[4,5,6][Level of evidence B3] The results of these trials were summarized in a systematic review.[8]

- At 5 to 6 months, the complete response rates in patients were 36 of 62 in the combined imiquimod arm versus 0 of 42 in the combined placebo arm, and the partial response rates were 18 of 62 in the combined imiquimod arm versus 1 of 42 in the combined placebo arm (relative risk, 11.95; 95% confidence interval, 3.21–44.51).

- In the only trial reporting progression to cancer at 12 months, there was no difference in progression rate, but the trial was severely underpowered because only 3 of the total 52 women developed invasive disease by 12 months.[6]

- The only trial reporting quality of life [6] showed no difference between imiquimod and placebo.

- Local side effects of imiquimod included pain, edema, erythema, and a single case of erosion. However, no patients had to discontinue treatment as a result of toxicity.

Other nonsurgical interventions

Nonsurgical approaches have been studied because of the physical and psychosexual morbidity associated with many vulvar surgical procedures. Some of these approaches, including topical fluorouracil, recombinant interferon gamma, bleomycin, and trinitrochlorobenzene, have been largely abandoned because of high recurrence rates or intolerable local side effects, such as pain, irritation, and ulceration.[8,16]

Photodynamic therapy, using topically applied 5-aminolevulinic acid as the sensitizing agent for 635 nm laser light, has also been studied. However, data are limited to small case series with variable response rates.[17,18][Level of evidence C3]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- van Seters M, van Beurden M, de Craen AJ: Is the assumed natural history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III based on enough evidence? A systematic review of 3322 published patients. Gynecol Oncol 97 (2): 645-51, 2005.

- Kaushik S, Pepas L, Nordin A, et al.: Surgical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD007928, 2011.

- von Gruenigen VE, Gibbons HE, Gibbins K, et al.: Surgical treatments for vulvar and vaginal dysplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 109 (4): 942-7, 2007.

- Sterling JC, Smith NA, Loo WJ, et al.: Randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial for treatment of high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia with imiquimod. [Abstract] J Eur Acad Derm Venereol 19 (Suppl 2): A-FC06.1, 22, 2005.

- Mathiesen O, Buus SK, Cramers M: Topical imiquimod can reverse vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised, double-blinded study. Gynecol Oncol 107 (2): 219-22, 2007.

- van Seters M, van Beurden M, ten Kate FJ, et al.: Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod. N Engl J Med 358 (14): 1465-73, 2008.

- Terlou A, van Seters M, Ewing PC, et al.: Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod: seven years median follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Gynecol Oncol 121 (1): 157-62, 2011.

- Pepas L, Kaushik S, Bryant A, et al.: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD007924, 2011.

- Sideri M, Jones RW, Wilkinson EJ, et al.: Squamous vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: 2004 modified terminology, ISSVD Vulvar Oncology Subcommittee. J Reprod Med 50 (11): 807-10, 2005.

- Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, et al.: The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Terminology of Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. J Low Genit Tract Dis 20 (1): 11-4, 2016.

- Jones RW, Rowan DM, Stewart AW: Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: aspects of the natural history and outcome in 405 women. Obstet Gynecol 106 (6): 1319-26, 2005.

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

- Küppers V, Stiller M, Somville T, et al.: Risk factors for recurrent VIN. Role of multifocality and grade of disease. J Reprod Med 42 (3): 140-4, 1997.

- Buscema J, Woodruff JD, Parmley TH, et al.: Carcinoma in situ of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 55 (2): 225-30, 1980.

- Jones RW, Rowan DM: Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III: a clinical study of the outcome in 113 cases with relation to the later development of invasive vulvar carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 84 (5): 741-5, 1994.

- Sillman FH, Sedlis A, Boyce JG: A review of lower genital intraepithelial neoplasia and the use of topical 5-fluorouracil. Obstet Gynecol Surv 40 (4): 190-220, 1985.

- Hillemanns P, Untch M, Dannecker C, et al.: Photodynamic therapy of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia using 5-aminolevulinic acid. Int J Cancer 85 (5): 649-53, 2000.

- Fehr MK, Hornung R, Schwarz VA, et al.: Photodynamic therapy of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III using topically applied 5-aminolevulinic acid. Gynecol Oncol 80 (1): 62-6, 2001.

Treatment Options for Stages I and II Vulvar Cancer

Treatment options for stage I and stage II vulvar cancer include the following:

- Surgery.

- Surgery and radiation therapy.

- Radiation therapy alone.

Surgery

Radical local excision with ipsilateral or bilateral inguinal and femoral lymph node dissection may be indicated. For stage I microinvasive lesions (<1 mm invasion) with no associated severe vulvar dystrophy, a wide (1 cm margin) excision (without lymph node dissection) may be done. For all other stage I lesions, if well lateralized, without diffuse severe dystrophy, and with clinically negative nodes, a radical local excision with complete unilateral lymphadenectomy may be done.[1] Candidates for this procedure should have lesions 2 cm or smaller in diameter with 5 mm or less invasion, no capillary-lymphatic space invasion, and clinically uninvolved nodes.[2,3]

For stage II disease, large T2* tumors may require modified radical vulvectomy or radical vulvectomy.[4]*T2 is defined as tumor confined to the vulva and/or perineum, more than 2 cm in greatest dimension.

For both stage I and stage II disease, radical local excision and sentinel node dissection is indicated and groin dissection is reserved for those with metastasis to the sentinel node(s).[5]

Surgery and radiation therapy

Some investigators recommend radical excision and groin nodal radiation therapy as a means to avoid the morbidity of lymph node dissection. However, it is not clear whether radiation therapy can achieve the same local control rates or survival rates as lymph node dissection in early-stage disease. A randomized trial to address this issue in patients with clinically localized vulvar disease was stopped early as a result of early emergence of worse outcomes in the radiation therapy arm.[6,7] For stage II disease, adjuvant local radiation therapy may be indicated for surgical margins smaller than 8 mm, capillary-lymphatic space invasion, and thickness greater than 5 mm.[8,9]

Radiation therapy alone

For patients unable to tolerate radical surgery or deemed ineligible for surgery because of the site or extent of disease, radical radiation therapy may be associated with favorable survival.[10,11,12,13]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Malfetano JH, Piver MS, Tsukada Y, et al.: Univariate and multivariate analyses of 5-year survival, recurrence, and inguinal node metastases in stage I and II vulvar carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 30 (2): 124-31, 1985.

- Stehman FB, Bundy BN, Dvoretsky PM, et al.: Early stage I carcinoma of the vulva treated with ipsilateral superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy and modified radical hemivulvectomy: a prospective study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Obstet Gynecol 79 (4): 490-7, 1992.

- Hacker NF, Van der Velden J: Conservative management of early vulvar cancer. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1673-7, 1993.

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

- Van der Zee AG, Oonk MH, De Hullu JA, et al.: Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early-stage vulvar cancer. J Clin Oncol 26 (6): 884-9, 2008.

- Stehman FB, Bundy BN, Thomas G, et al.: Groin dissection versus groin radiation in carcinoma of the vulva: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 24 (2): 389-96, 1992.

- van der Velden J, Fons G, Lawrie TA: Primary groin irradiation versus primary groin surgery for early vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5): CD002224, 2011.

- Thomas GM, Dembo AJ, Bryson SC, et al.: Changing concepts in the management of vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol 42 (1): 9-21, 1991.

- Faul CM, Mirmow D, Huang Q, et al.: Adjuvant radiation for vulvar carcinoma: improved local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 38 (2): 381-9, 1997.

- Petereit DG, Mehta MP, Buchler DA, et al.: Inguinofemoral radiation of N0,N1 vulvar cancer may be equivalent to lymphadenectomy if proper radiation technique is used. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 27 (4): 963-7, 1993.

- Slevin NJ, Pointon RC: Radical radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Radiol 62 (734): 145-7, 1989.

- Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Galakatos A, et al.: Radiation therapy in management of carcinoma of the vulva with emphasis on conservation therapy. Cancer 71 (11): 3707-16, 1993.

- Kumar PP, Good RR, Scott JC: Techniques for management of vulvar cancer by irradiation alone. Radiat Med 6 (4): 185-91, 1988 Jul-Aug.

Treatment Options for Stage III Vulvar Cancer

Treatment options for stage III vulvar cancer include the following:

- Surgery with or without radiation therapy.

- Radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery.

- Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy.

Surgery with or without radiation therapy

Modified radical or radical vulvectomy with inguinal and femoral lymphadenectomy is the standard therapy.[1] Nodal involvement is a key determinant of survival. Radiation therapy is given to patients with large primary lesions and narrow margins. Radiation therapy to the pelvis and groin is given if inguinal lymph nodes are positive.[2] Radiation therapy to the pelvis and groin is usually given if two or more groin nodes are involved.[2,3]

Localized adjuvant radiation therapy consisting of 45 Gy to 50 Gy may also be indicated when there is capillary-lymphatic space invasion and a thickness of greater than 5 mm, particularly if the nodes are involved.[1]

Radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery

Preoperative neoadjuvant radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy may be used to improve operability and even decrease the extent of surgery required.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy

For patients unable to tolerate radical surgery or deemed ineligible for surgery because of the site or extent of disease, radical radiation therapy may be associated with long-term survival.[11,12] Some physicians prefer to add concurrent fluorouracil (5-FU) or 5-FU and cisplatin.[1,13]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Thomas GM, Dembo AJ, Bryson SC, et al.: Changing concepts in the management of vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol 42 (1): 9-21, 1991.

- Kunos C, Simpkins F, Gibbons H, et al.: Radiation therapy compared with pelvic node resection for node-positive vulvar cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 114 (3): 537-46, 2009.

- Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al.: Prognostic factors for groin node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study) Gynecol Oncol 49 (3): 279-83, 1993.

- Boronow RC, Hickman BT, Reagan MT, et al.: Combined therapy as an alternative to exenteration for locally advanced vulvovaginal cancer. II. Results, complications, and dosimetric and surgical considerations. Am J Clin Oncol 10 (2): 171-81, 1987.

- Anderson JM, Cassady JR, Shimm DS, et al.: Vulvar carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 32 (5): 1351-7, 1995.

- van Doorn HC, Ansink A, Verhaar-Langereis M, et al.: Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for advanced primary vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD003752, 2006.

- Eifel PJ, Morris M, Burke TW, et al.: Prolonged continuous infusion cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with radiation for locally advanced carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 59 (1): 51-6, 1995.

- Landoni F, Maneo A, Zanetta G, et al.: Concurrent preoperative chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C and radiotherapy (FUMIR) followed by limited surgery in locally advanced and recurrent vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 61 (3): 321-7, 1996.

- Montana GS, Thomas GM, Moore DH, et al.: Preoperative chemo-radiation for carcinoma of the vulva with N2/N3 nodes: a gynecologic oncology group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 48 (4): 1007-13, 2000.

- Moore DH, Thomas GM, Montana GS, et al.: Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 42 (1): 79-85, 1998.

- Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Galakatos A, et al.: Radiation therapy in management of carcinoma of the vulva with emphasis on conservation therapy. Cancer 71 (11): 3707-16, 1993.

- Slevin NJ, Pointon RC: Radical radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Radiol 62 (734): 145-7, 1989.

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

Treatment Options for Stage IVA Vulvar Cancer

Treatment options for stage IVA vulvar cancer include the following:

- Surgery.

- Surgery and radiation therapy.

- Radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery.

- Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy.

Surgery

Radical vulvectomy and pelvic exenteration may be indicated for patients with stage IVA vulvar cancer.

Surgery and radiation therapy

Surgery followed by radiation therapy may be done for large resected lesions with narrow margins. Localized adjuvant radiation therapy consisting of 45 Gy to 50 Gy may also be indicated when there is capillary-lymphatic space invasion and thickness greater than 5 mm.[1] Radiation therapy to the pelvis and groin is given if two or more groin lymph nodes are involved.[2,3]

Radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery

Neoadjuvant radiation therapy or chemoradiation therapy of large primary lesions (to improve operability) may be done, followed by radical surgery.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy

For patients unable to tolerate radical vulvectomy or who are deemed ineligible for surgery because of the site or extent of disease, radical radiation therapy may be associated with long-term survival.[11,12] When radiation therapy is used for primary definitive treatment of vulvar cancer, some physicians prefer to add concurrent fluorouracil (5-FU) or 5-FU and cisplatin.[1,13,14,15,16,17]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Thomas GM, Dembo AJ, Bryson SC, et al.: Changing concepts in the management of vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol 42 (1): 9-21, 1991.

- Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al.: Radiation therapy versus pelvic node resection for carcinoma of the vulva with positive groin nodes. Obstet Gynecol 68 (6): 733-40, 1986.

- Kunos C, Simpkins F, Gibbons H, et al.: Radiation therapy compared with pelvic node resection for node-positive vulvar cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 114 (3): 537-46, 2009.

- Boronow RC, Hickman BT, Reagan MT, et al.: Combined therapy as an alternative to exenteration for locally advanced vulvovaginal cancer. II. Results, complications, and dosimetric and surgical considerations. Am J Clin Oncol 10 (2): 171-81, 1987.

- Anderson JM, Cassady JR, Shimm DS, et al.: Vulvar carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 32 (5): 1351-7, 1995.

- van Doorn HC, Ansink A, Verhaar-Langereis M, et al.: Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for advanced primary vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD003752, 2006.

- Eifel PJ, Morris M, Burke TW, et al.: Prolonged continuous infusion cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with radiation for locally advanced carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 59 (1): 51-6, 1995.

- Landoni F, Maneo A, Zanetta G, et al.: Concurrent preoperative chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C and radiotherapy (FUMIR) followed by limited surgery in locally advanced and recurrent vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 61 (3): 321-7, 1996.

- Montana GS, Thomas GM, Moore DH, et al.: Preoperative chemo-radiation for carcinoma of the vulva with N2/N3 nodes: a gynecologic oncology group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 48 (4): 1007-13, 2000.

- Moore DH, Thomas GM, Montana GS, et al.: Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 42 (1): 79-85, 1998.

- Slevin NJ, Pointon RC: Radical radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Radiol 62 (734): 145-7, 1989.

- Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Galakatos A, et al.: Radiation therapy in management of carcinoma of the vulva with emphasis on conservation therapy. Cancer 71 (11): 3707-16, 1993.

- Russell AH, Mesic JB, Scudder SA, et al.: Synchronous radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy for locally advanced or recurrent squamous cancer of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 47 (1): 14-20, 1992.

- Berek JS, Heaps JM, Fu YS, et al.: Concurrent cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage squamous carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 42 (3): 197-201, 1991.

- Koh WJ, Wallace HJ, Greer BE, et al.: Combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the management of local-regionally advanced vulvar cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 26 (5): 809-16, 1993.

- Thomas G, Dembo A, DePetrillo A, et al.: Concurrent radiation and chemotherapy in vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 34 (3): 263-7, 1989.

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

Treatment Options for Stage IVB Vulvar Cancer

There is no standard treatment approach in the management of stage IVB vulvar cancer.

Local therapy must be individualized depending on the extent of local and metastatic disease.

There is no standard chemotherapy for metastatic disease, and reports describing the use of this modality are anecdotal.[1] However, by largely extrapolating from regimens used for anal or cervical cancer, chemotherapy has been studied. Regimens have included various combinations of fluorouracil, cisplatin, mitomycin, or bleomycin.[1,2,3] Given the advanced age and comorbidity of many patients with advanced or recurrent vulvar cancer, patient tolerance is a major consideration in the use of these agents.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

- van Doorn HC, Ansink A, Verhaar-Langereis M, et al.: Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for advanced primary vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD003752, 2006.

- Cormio G, Loizzi V, Gissi F, et al.: Cisplatin and vinorelbine chemotherapy in recurrent vulvar carcinoma. Oncology 77 (5): 281-4, 2009.

Treatment Options for Recurrent Vulvar Cancer

Treatment options for recurrent vulvar cancer include the following:

- Wide local excision with or without radiation therapy in patients with local recurrence.

- Radical vulvectomy and pelvic exenteration in patients with local recurrence.

- Synchronous radiation therapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy with or without surgery.[1]

Treatment and outcome depend on the site and extent of recurrence.[2] Radical excision of localized recurrence may be considered if technically feasible.[3] Palliative radiation therapy is used for some patients. Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy may be associated with substantial disease-free periods in some patients with a small local recurrence.[1,4,5] When local recurrence occurs more than 2 years after primary treatment, a combination of radiation therapy and surgery may result in a 5-year survival rate of greater than 50%.[6,7]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Russell AH, Mesic JB, Scudder SA, et al.: Synchronous radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy for locally advanced or recurrent squamous cancer of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 47 (1): 14-20, 1992.

- Piura B, Masotina A, Murdoch J, et al.: Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a study of 73 cases. Gynecol Oncol 48 (2): 189-95, 1993.

- Hopkins MP, Reid GC, Morley GW: The surgical management of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 75 (6): 1001-5, 1990.

- Miyazawa K, Nori D, Hilaris BS, et al.: Role of radiation therapy in the treatment of advanced vulvar carcinoma. J Reprod Med 28 (8): 539-41, 1983.

- Thomas G, Dembo A, DePetrillo A, et al.: Concurrent radiation and chemotherapy in vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 34 (3): 263-7, 1989.

- Podratz KC, Symmonds RE, Taylor WF, et al.: Carcinoma of the vulva: analysis of treatment and survival. Obstet Gynecol 61 (1): 63-74, 1983.

- Shimm DS, Fuller AF, Orlow EL, et al.: Prognostic variables in the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 24 (3): 343-58, 1986.

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

General Information About Vulvar Cancer

Updated statistics with estimated new cases and deaths for 2024 (cited American Cancer Society as reference 3).

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of vulvar cancer. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Vulvar Cancer Treatment are:

- Fumiko Chino, MD

- Marina Stasenko, MD (New York University Medical Center)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Vulvar Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/vulvar/hp/vulvar-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389203]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us.

Last Revised: 2024-02-16

Topic Contents

- General Information About Vulvar Cancer

- Cellular Classification of Vulvar Cancer

- Stage Information for Vulvar Cancer

- Treatment Option Overview for Vulvar Cancer

- Treatment of Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia (VIN)

- Treatment of Stages I and II Vulvar Cancer

- Treatment of Stage III Vulvar Cancer

- Treatment of Stage IVA Vulvar Cancer

- Treatment of Stage IVB Vulvar Cancer

- Treatment of Recurrent Vulvar Cancer

- Latest Updates to This Summary (02 / 16 / 2024)

- About This PDQ Summary

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.